Indonesian graphic designers—along with artists from around the globe—banded together to help their own after the 2004 tsunami devastated their homeland.

ALLEVIATING CRISES THROUGH PROPAGANDA

by Ismiaji Cahyono

In the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami, Indonesian graphic designers joined together and emerged as activists for social and political change. I became involved in the Indonesian Graphic Design Forum (FDGI) in July 2005, an organization that spearheaded some notable design events to raise awareness and aid in recovery efforts for victims of the tsunami.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

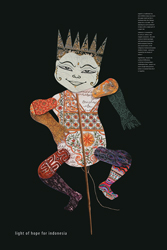

LIGHT OF HOPE FOR INDONESIA posters designed by various designers worldwide are shown throughout. ABOVE: Sakti Makki, Indonesia.TSUNAMI: A CATALYST TO CHANGE

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The 29-year armed conflict in Aceh between the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) and the Indonesian government—which victimized thousands of civilians—was suspended on Dec. 26, 2004, when the tsunami devastated the region. The Aceh earthquake sent its tsunami waves across nations, sweeping away certain coasts of Thailand, India, Sri Lanka, and Africa, killing hundreds of thousands and uprooting the lives of millions. Ironically this was the catalyst to the road to peace between the two opposing parties.

Opening its doors to international aid, visual communications initially played a crucial role in the recovery efforts in Indonesia by exposing the crisis through mass media to the world with vivid images of human tragedy to increase awareness, sympathy, and ultimately raise funds. “The broadcasts were heartbreaking. But seeing this repeated every day for months was enough! It’s about the people of Aceh. Their tragedy is being exploited,” confided Paulus, a local architect.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Hermawan Tanzil, Indonesia.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Board for Aceh and Nias (BRR) was formed by the government and participating national and international organizations on April 16, 2005. It was a unified effort to channel collected funds to the victims, rebuild infrastructure and housing, and help revive the regional economy by generating trade and commerce.

Local designers and artists did their own part to support Aceh’s recovery. One of the most exceptional events was a poster exhibition organized by FDGI, called Light of Hope for Indonesia, which took place Sept. 7–11, 2005. Its purpose was to encourage and motivate hope among the victims of the tragedy by communicating positive messages. Most critics recognize propaganda as a negative or more aggressively manipulative form of communication that persuades or influences large masses into acting according to the intended agenda of the communicator. According to Lucy Lippard in Propaganda for Propaganda, however, propaganda can be positive by being socially and aesthetically aware, provoking a new way of seeing and thinking about what goes on around us. “In presenting the suffering caused by the tsunami so far, the mass media has played on our bloodlust,” Alex Supartono explains in The Faces of Survivors.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Apex Lin Pong-Soong, Taiwan.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Light of Hope avoided using gruesome visuals because it intended to heal instead of frighten or prolong trauma. This “new way of seeing” proliferated hope and motivation as a spiritual therapy. The exhibition was also a relevant example of how visual communication can independently advocate socially and politically by collaborating with private and international sources for a regional cause. The FDGI benefited as well from that campaign, acquiring recognition and support for furthering its organizational agenda. Of course, it makes one wonder what was being propagated—the posters, the designers, the messages, the organization, or all of the above?

IN THE MARGINS: REACTIVE VISUAL ARTS IN INDONESIA

Contemporary Indonesian art arose from the desire to defend against aggression. From 1945–1949 poster and mural artists initiated resistance against recolonization. (The Dutch colonized Indonesia for 350 years until 1942, losing it to Japan. The Japanese surrendered Indonesia to Allied Forces in 1945). In guerilla fashion, the artists encouraged activism using poetic images of contemplation as well as illustrating patriotism, heroism, and perseverance. After the “independence revolution,” the arts and the government began a love-hate relationship. The Indonesian government found the arts to be instrumental for political campaigns, but when social realism reached its zenith in the mid 1960s, the newly installed dictatorial government of Soeharto (aka Suharto) began censoring the arts. It violently shut down and muted many “reactionary” artistic movements, like the socialist LEKRA movement. Despite heavy monitoring and censorship, the 1970s and ’80s “Gerakan Seni Rupa Baru”—the New Art Movement—reintroduced the arts into social and political experiences. Social reflective art blossomed after Soeharto resigned in 1998.

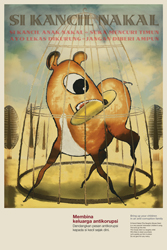

Indonesian artists and designers, many of whom were once social and political activists, survived by going commercial. Over time some even established celebrity status. Some critics argued that this was a good thing. It enabled the artist to flexibly move around the system. From the perspective of visual engagement in social activist causes, this notion would have been more encouraging if all artists had been socially conscious. But there has not been a significant social campaign through the arts in Indonesia in the last decade, and now artists have been challenged with censorship and pornography laws—for example, public demonstrations against the release of Playboy magazine in Indonesia and the “Pinkswing Park” fine art installation piece—adding a new urgency to questions about the functions of art and design in politics and culture.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Ian Perkins, London.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

PROMOTING PEACE AND HOPE

Founded in 2001, the FDGI is a small community of relatively young Indonesian graphic designers and educators with an agenda to empower the graphic design profession by encouraging participation in social, cultural, and educational activities. They have organized free lectures and seminars for students, national scale seminars for professionals, campus workshops, exhibitions, and have distributed periodicals. In June 2003, the FDGI conducted a poster exhibition—which featured 50 local designers, mostly students—titled Looking at a Peaceful Indonesia in response to 9/11 and the first Bali bombing. Despite negative reviews, this event marked an Indonesian design revival. The last major design event was an international poster exposition held by the Indonesian Graphic Design Association (IPGI) in collaboration with the Japanese Graphic Design Association (JAGDA) in 1983.

“Shortly after the tsunami, I presented the idea of a poster exhibition, but it quickly diminished from lack of support,” says FDGI cofounder Hastjarjo B. Wibowo. The idea was revived when a consortium of graphic technology producers, the FGD, offered space in their biannual exposition. “This was an excellent opportunity for us to build our brand, a key to network and access for future activities,” he adds. A bigger goal and concept had to be drawn up for the exhibition. FDGI wanted to avoid the mass media strategy of depicting destruction and tragedy. The tsunami represented the accumulation of crises that Indonesia has had to face in the last decade and encouragement or motivation was what people needed instead of portraying devastation. The prolonged crises became the bigger theme, but the content was morally motivational, a positive propaganda.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

David Carson, Charleston, S.C.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

With less than two months to organize the exhibition, certain ethical submission requirements—such as calling for entries—had to be sacrificed. We felt this exhibition needed to be ambitious, so we proposed that international designers be invited to participate. The tsunami was, after all, an international disaster. “Foreign designers must be included to provide a different perspective of Indonesia and also establish communication with them,” Wibowo acknowledged.

Through lobbying and persistent correspondence, 66 designers from 17 countries agreed to participate in the event, including Milton Glaser, Seymour Chwast, David Carson, Luba Lukova, Rick Valicenti, Nancy Skolos, and Karlssonwilker, among others. Leading Indonesian designers included Hermawan Tanzil, Iwan Ramelan, Danton Sihombing, Priyanto Sunarto, Irvan Noeman, T, Sutanto, Sakti Makki, and many more. Designers from as far as Iran, South Korea, Taiwan, India, Thailand, and neighboring countries such as Malaysia, U.K., and Australia also participated. A discussion held on the exhibition at Institut Teknologi Bandung on Oct. 21, 2005, concluded that the quality of the posters was difficult to measure. Unlike advertising posters, the Light of Hope target audience was vague, and the designers’ involvement and commitment to the cause was also unpredictable.

“It would be odd to apply the variety of foreign cultural codes used in communicating the posters to Indonesia,” panelist Priyanto Sunarto confided. One example is “Wing of Life,” contributed by Taiwanese designer Aphex Lin—a sequential depiction of a cross morphing into a flying dove, the symbol of peace. Sunarto argued, “The context of the cross signifying death contains an alien meaning to the Aceh people, because the dead there weren’t buried with cross markers. Here, contextualizing the messages in the local culture was imperative.” In contrast, a poster by Ian Perkins of London used universal symbols in simple and minimal forms—a red heart with a rectangular cutout on its edge. The cutout piece formed the Indonesian flag of red and white, which communicated succinctly that Indonesia needs more heart. Luba Lukova’s poster was deemed by the panel as distinctly “Luba Lukova”—the designer both creatively amusing herself as well as conveying a message. Her usage of the universal symbol—the gecko’s severed tail—as an object of regeneration is communicative among the Indonesian audience.

Most of the local artists took the path of “contemplation.” For example, Hermawan Tanzil’s poster of a traditional puppet is decorated with various ethnic motifs signifying urgency to forget differences in order to recover from the tsunami. Or the poster by Lans Brahmantyo, which illustrated a glowing womb of a pregnant woman, identifying hope through regeneration. The poster by Wagiono appropriated a photograph of a pebble as symbol for lightness, strength, and hope. The exhibition boasted the largest graphic exposition in Southeast Asia drawing a record-breaking crowd. After the expo, the FDGI was invited to exhibit the posters in four major cities in Indonesia—Bandung, Surabaya, Yogyakarta, and Aceh.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Danton Sihombing and Ilma Noeman, Indonesia.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

“There are many plans for the donated posters: One is to communicate the moral messages to a larger audience. Right now we are looking for sponsors to support this. There are also demands for organizing a bigger event, such as the first Indonesian Poster Biennial,” Wibowo explains. The BRR invited FDGI to exhibit the posters in Aceh and also requested it contribute a research team of graphic designers and students as part of the reconstruction consortium. The research team will investigate communication methods most effective for the Aceh people when dealing with future disasters such as evacuation and survival plans, and hygiene and sanitation procedures.

The FDGI and its small community of designers have achieved some much-desired and hard-to-reach goals. With few resources, it created an intelligent international and regional network and paved a road for future designers to advocate for the profession and its community. With graphic design awakened and available channels and sources open for it to be socially and politically engaged, the hope for future socially conscious Indonesian designers is secured. And perhaps through graphic design the prolonged crises in Indonesian economy and society can be ameliorated.

Source: STEP Inside Design Magazine

•••

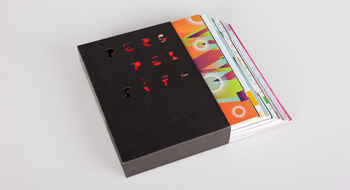

1. Nirmana: Elemen-elemen Seni dan Desain | Sadjiman Ebdi Sanyoto

1. Nirmana: Elemen-elemen Seni dan Desain | Sadjiman Ebdi Sanyoto 2. Desain Komunikasi Visual Terpadu | Yongky Safanayong

2. Desain Komunikasi Visual Terpadu | Yongky Safanayong 3. Hurufontipografi | Surianto Rustan

3. Hurufontipografi | Surianto Rustan www.underconsideration.com

www.underconsideration.com